When you enter a building, have you ever considered how it remains standing? The walls, the roof, and the beams supporting the floors are not there by chance. Every architectural design is supported by a powerful, unseen system that works continuously to maintain its stability. As buildings become more complex, so does the intricacy of this underlying structural framework.

Let’s explore the development of building structures, from basic wooden houses to tall city towers and even large cultural halls with seemingly floating roofs. We will examine how materials, forces, and design choices evolve, not only to support weight but also to respond to the climate, culture, and human needs.

Simple Buildings: The Basics of Engineering

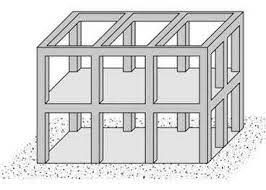

In small-scale construction, such as a rural house, a pavilion, or a simple workshop, the structure often relies on fundamental principles. Common systems include the post-and-lintel (a vertical support holding a horizontal beam) or platform framing, where wooden studs form walls and frames support floors.

These systems are simple, affordable, and easy to build, especially with local materials like timber or bamboo. However, they have clear limitations: when the span becomes too large, or when the load increases, components may bend or fail. This is why traditional construction limits the spacing between supports. A wooden beam might span only 3 to 5 meters before needing additional reinforcement.

These early forms are still relevant today. In low-cost housing and sustainable design, minimalist systems using local timber or bamboo are being reconsidered, with modern calculations and improved connections to ensure safety [1].

Mid-Rise Buildings: The Role of Columns and Beams

As buildings grow taller, typically 4 to 10 stories, the load on each structural element significantly increases. Individual posts can no longer support the combined weight of the floors, walls, and roof. This is where structural frames become essential.

In mid-rise buildings, common systems include moment frames or braced frames. In these systems, beams and columns are connected with rigid joints, allowing them to resist both vertical loads and lateral forces, such as wind or earthquakes. The connections between beams and columns are crucial; they must be strong enough to transfer bending forces without deforming.

Steel and reinforced concrete are preferred materials because they can handle high tension and compression. In Indonesia, for example, many apartment buildings in cities like Medan, Bandung, or Surabaya use reinforced concrete frames, with columns spaced every 4 to 6 meters to balance strength and usable floor space [2].

However, even with these robust systems, careful planning by engineers is vital. A column that is too thin might buckle under load. Beams that are not deep enough will sag over time. If connections are not detailed precisely, the building’s performance during seismic events—a serious concern in earthquake-prone regions like Indonesia—could be severely compromised.

High-Rise Buildings: Managing Wind and Gravity

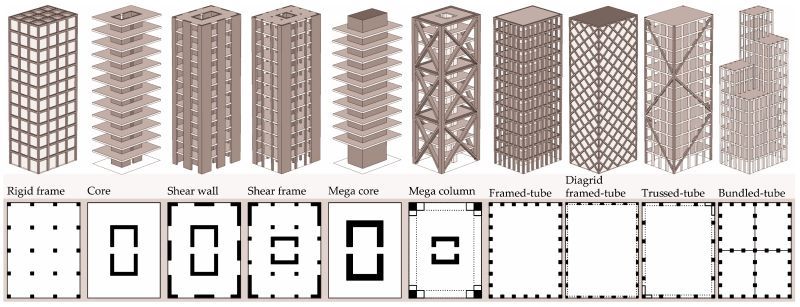

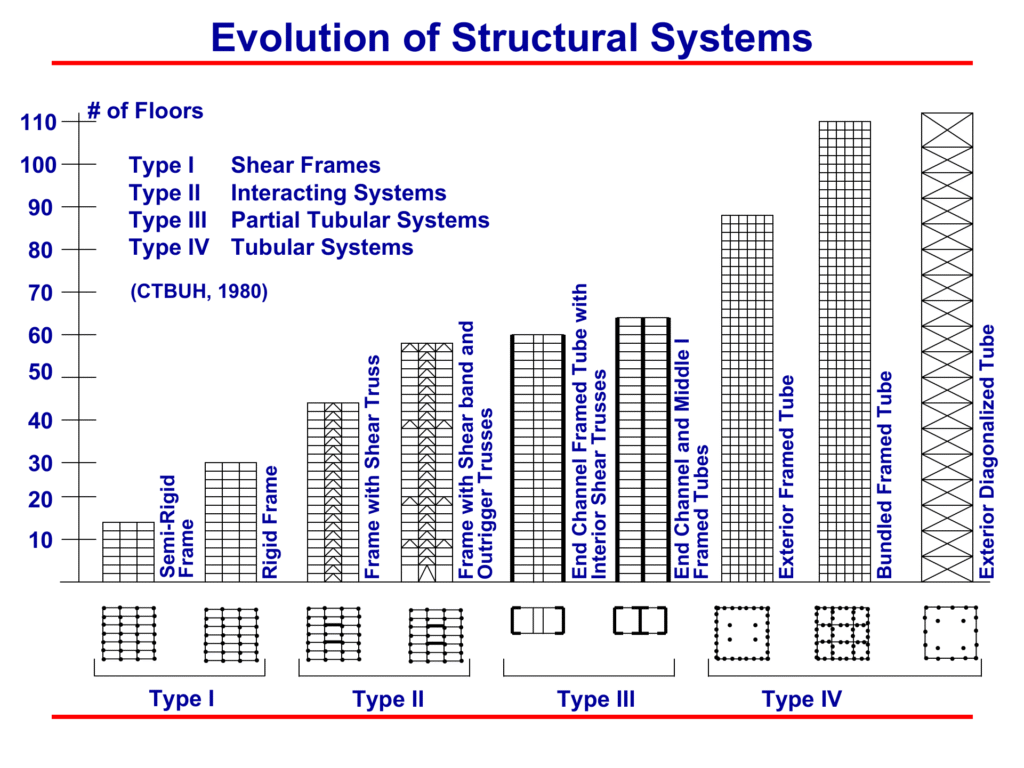

Consider a structure reaching 50 or even 100 floors. The forces acting on it go beyond just supporting weight; they include critical considerations for stability against strong winds, controlled movement during earthquakes, and efficient use of space. This is where advanced structural solutions are needed.

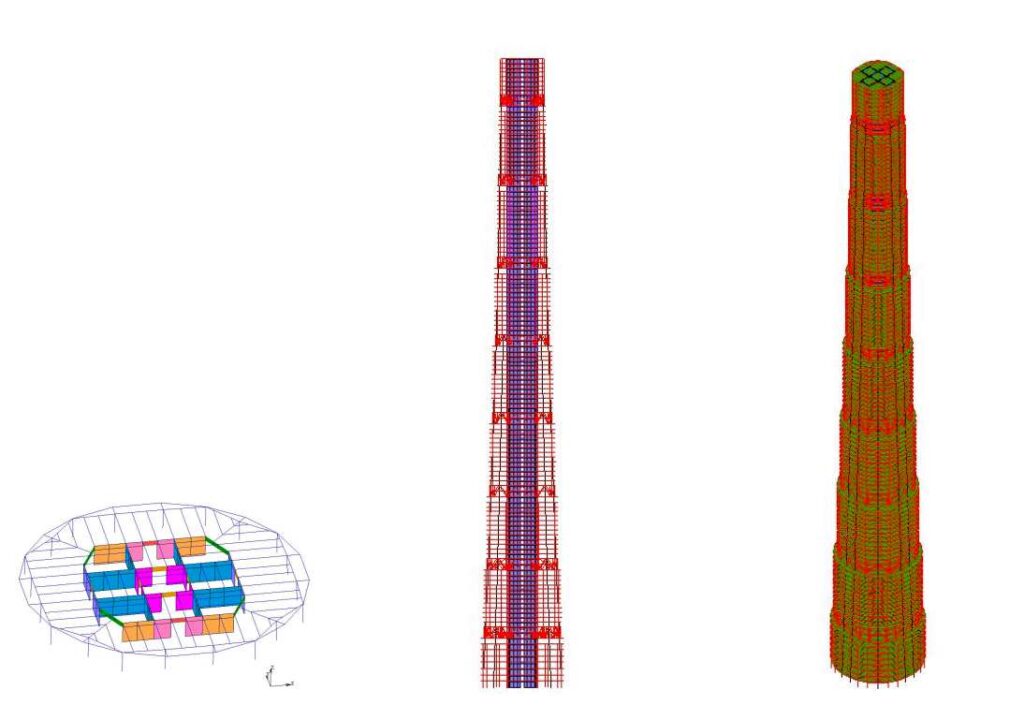

In high-rise architecture, the structure evolves into a sophisticated system with vertical cores, outrigger trusses, and often, tuned mass dampers. A central core, usually made of reinforced concrete, acts as the building’s main support, carrying vertical loads and resisting lateral forces. Outriggers are horizontal truss systems that connect this central core to the outer columns, significantly stiffening the entire structure.

One notable innovation is the tuned mass damper—a large weight suspended inside the building, designed to gently swing opposite to the building’s swaying motion caused by wind. For instance, the Taipei 101 tower uses a 660-ton steel sphere that moves against the building’s sway, reducing movement by up to 40% [3].

Despite these advanced systems, designers still face the challenge of creating structures that are both strong and flexible, while also allowing for open and adaptable floor plans. This is why modern high-rises often use composite structures, combining steel frames with concrete slabs for superior strength and faster construction.

Wide-Span Structures: Blending Architecture and Engineering

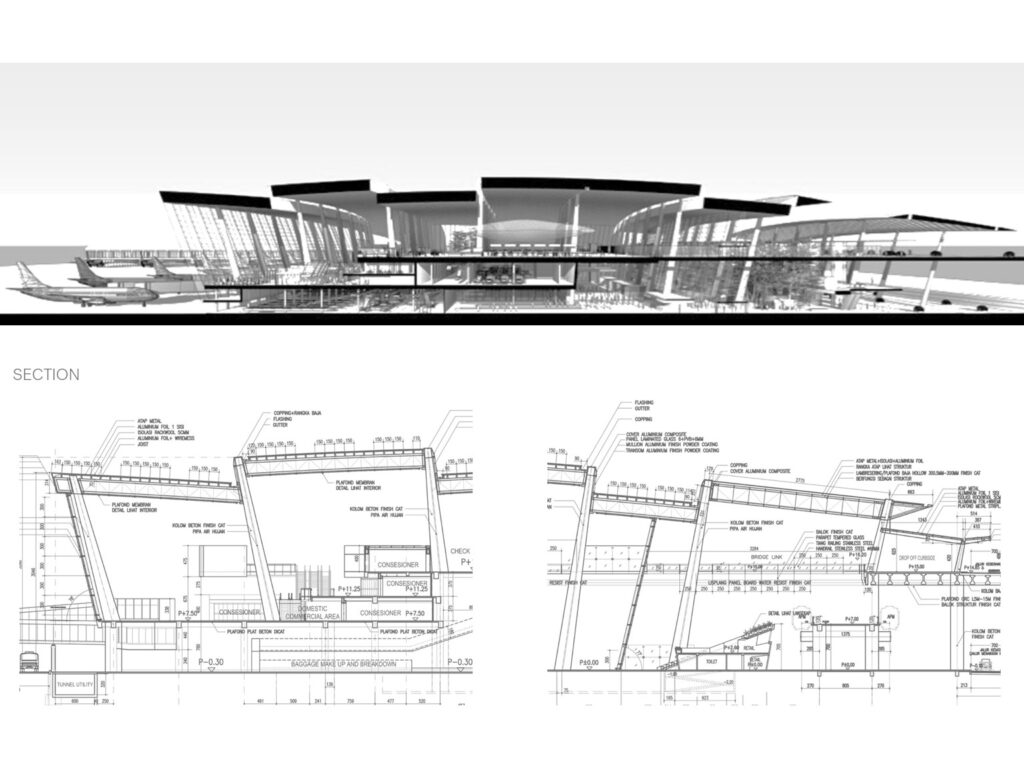

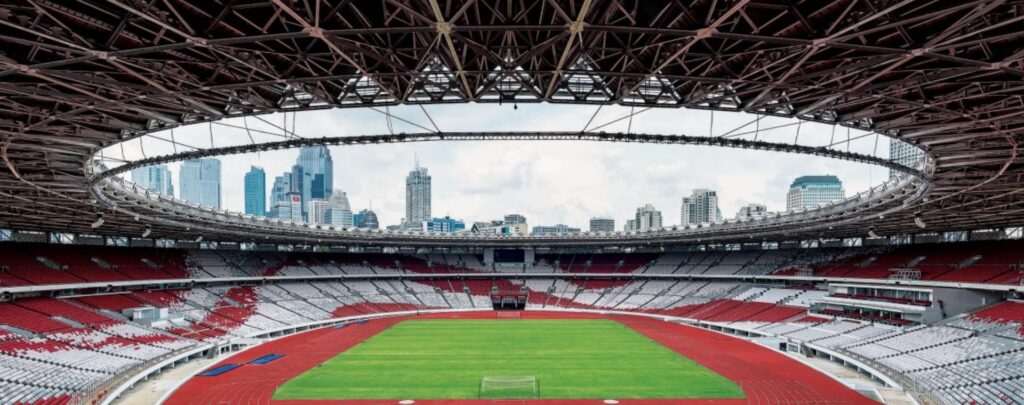

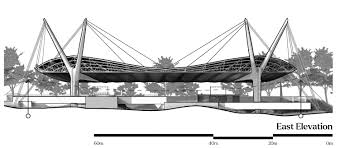

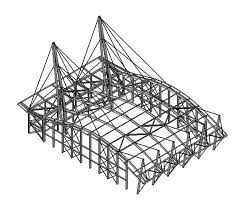

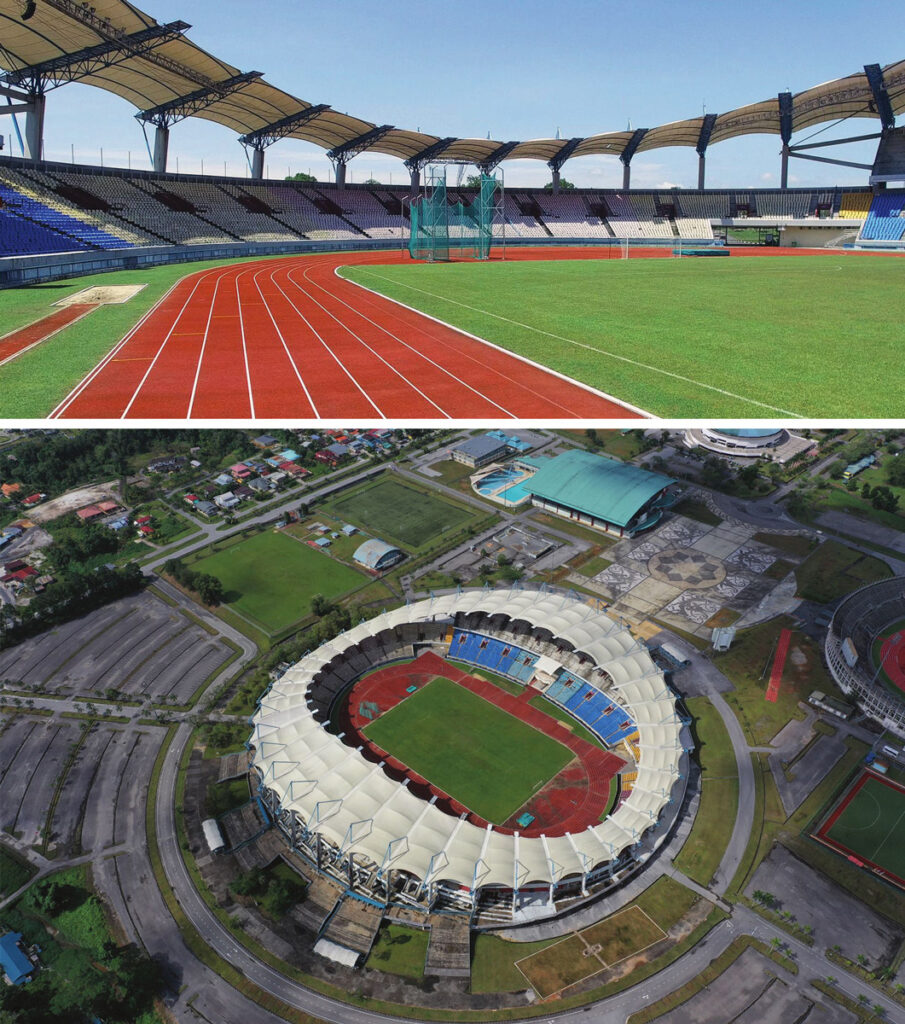

Now, let’s look at a different type of architectural space—large areas like convention centers, sports stadiums, airport terminals, or grand mosques with massive domes. These buildings do not need tall columns or rigid frames because the primary goal is to cover vast areas without internal supports. The main challenge here is achieving spatial freedom.

This is where the ingenuity of trusses, arches, cables, and membrane structures becomes apparent:

- A truss is an efficient geometric system of triangles that distributes loads effectively. Imagine a roof made of steel beams arranged in a ladder-like pattern.

- An arch utilizes compression to direct downward forces to its supporting bases. The Colosseum in Rome is a classic example of this principle.

- Cable-supported structures, like those found in stadium roofs, rely on the tension in steel cables to hold up the roof, requiring minimal support at the edges.

- Membrane structures, such as tensile roofs made from coated fabric, are light, flexible, and strong, making them ideal for covering large areas with minimal material [4].

An excellent example is the Sarawak Stadium roof in Malaysia, which uses a cable-net system spanning over 150 meters without any central support. This creates a remarkable sense of openness and freedom for spectators.

The key insight here is that the structure is more than just a collection of parts; it functions as a high-performing system. Every element—from material choice to connection details and overall geometry—works together seamlessly to achieve both optimal function and aesthetic appeal.

Common Thread: The Designer’s Essential Role

Regardless of scale or complexity, one truth remains: architects do not merely draw buildings; they engage with the principles of physics.

As a designer, you are a problem-solver who constantly asks: How can we support this load? How do we prevent unwanted movement? How do we ensure safety, efficiency, and beauty simultaneously? This is a significant intellectual challenge.

As structures become more intricate, the need for collaboration increases. This involves working closely with structural engineers, MEP (Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing) specialists, contractors, and clients. The buildings you design today must be constructible, functional, and safe, not just in theory but in reality.

This highlights why today’s architecture students must go beyond basic CAD sketches. We need to develop a deep understanding of:

- How various materials behave under different stresses (tension, compression, shear).

- The mechanisms by which connections transfer forces.

- How local building codes (such as SNI in Indonesia or IBC in the US) influence design decisions.

- The use of digital tools like ETABS, SAP2000, or Revit to analyze these complex loads before construction begins.

References

- Kharrazi, M. et al. (2020). Sustainable Timber Framing in Low-Cost Housing: A Case Study in Indonesia. 🌐 https://www.mdpi.com/2075-5309/10/10/836

- SNI 03-1729-2002 – Design of Concrete Structures (Indonesian National Standard). 🌐 https://standartsni.go.id/

- Lin, C.-C. & Chou, C.-C. (2006). Seismic Response of the Tuned Mass Damper at Taipei 101. 🌐 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0141029605002351

- Oberaigner, L. (2015). Tensile and Composite Structures: Design and Construction. 🌐 https://www.asce.org/

- IBC 2021 – International Building Code – Chapter 16 (Structural Design). 🌐 https://codes.iccsafe.org/content/IBC2021/chapter-16-structural-design